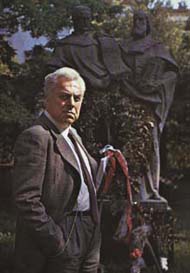

The Greatest bass of all time

18 May 1914, Plovdiv - 28 June 1993, Rome

The greatest Bulgarian of XXc. or how Boris Christoff is refused to play the part of the Tsar Samuil in the Macedonian opera.

The people who had intimate knowledge of the world-famous opera singer Boris Christoff, told, that his patriotism was great. The actor`s family came from of Macedonian lands and the great bass all life is kept in his heart the romantic love to these old Bulgarian lands.

In 1968, Boris Christoff lives in Italia. He received a letter from unknown composer from Scopie ( then Yugoslavia ). He reported, of the celebrity bass, is composed the sitorical opera with subject for the life and death of Tsar Samuil. After he made comliments for Bulgarian`s mastery the author offered him to perform the role of Samuil ( the star basso part ) in the future "opera performance" of the Scopie national theatre.

It's obvious that, the letter in question is harmonized with official Yugoslavian power in Belgrad. To Boris Christoff is extended invitations hot only for participations in tha musical composition, but and promises for generous fees, the gramophone reserves and very much glory along the performance of the Samuil's arias. The great opera singer is interested from the creation on the young scopian composer and he is agreed to see musical score and libretto.

Soon, the notes and words on the opera "Tsar Samuil" arrived in Italy in voluminous envelope and Boris Christoff conscientionsly is asq hainted with the htme, subject and music on the future performance.

Even when he read the beggining of the opera, the greatestworld and Bulgareian bass on the all times, understood, thes was forged document of the Bulgarian history. The Bulgarian Tsar Samuil was produced as "Macedonian duke", and his boyars as elite of the invented from Yugoslavian propaganda "Macedonian nation".

The anger of Boris Christoff is wented immediately in a harshly letter-answer to the young composer from Macedonia:

"Mr Macedonski,

I recived program for your "Tsar Samuil" for Scopie scene. I couldn't unterstand why you sent it to me. You know long ago, my opinion which is opinion of on every Bulgarian. Probluce a painful impression to me, the preface of D.Tashkovsky which is full with absurd ratiocinations and ditorted historic truths, which can't to redeuce impression even of the ingnoratnt people.

You know, my family come from parts of Bulgaria, in which you live and wich is called Macxedonia, which was and will be a centre of the most common bulgarian national spirit , as King Samuil Was and will stick in wolrd hisoty THE KING BULGARIAN,.

I wish you and your familly Happy New Year.

Boris Christoff

12th January 1969

D.Tashovsky is one of the angrist disposed macedonian historian, who every where publishes lies and defamations for Bulgaria.

The opera offer from Scopie deeply in concerned Boris Christoff because ofter, a few months ( on 1st September 1969 ) he wrote in this connection the outrageous letter to his fellow-student Lyuben Zhivkov:

"...This winter the composer Macedonsky sent me one program from, the first-hight performance of the Tsar Samuil in Macedonian national theatre in Scopie. I send you attacked to the letter photo-copy from the preface to the program - a case of the official treason to generation, mother-land and human worth and photo-copy of my short letter-answer in from without - comment, I want to you, I will suffer, unless I see there two bulgarian creatures ( Macedonsky and Tashkovky ) to wring their necks, to pull out their ears and send them to blazes with massive and holy kick- Good Lord, calm your slave, Boris!"

After angry reaction from aside of the great singer to the scopian forgers, from there they keep silent. Didn't follow any sign - nor an apology, notyet an explanation.

Today, nabody isn't remembered for opera "Tsar Samuil" whre the born in the imagination of author "macedonian Knyaz" must replace "BULGARIAN TSAR".

P.s.

Let don't remember, there high patriotic words pronounced in 1969, are saw in period when Bulgaria is governed from the Bulgarian communist party, under the influence on the Comintern and the decisions accepted from the "brotherly" Communist parties from socialist camp, recognized official the existence of the Macedonian country and Macedonian nation.

Even in the passports on the Bulgarian from Pirin land is enter: Nationality - Macedonian.

This more raise up the crystal clear patriotism of Boris Christoff.

In 1976 the great bass, "who never left Bulgaria in his feelings", dedicatedly extends the sacred traditions of the our old founders. He is actuated by the his love of the motherland, he is happy to do something else good for his mother country. With empathy and with his wefe's approval Mrs Franka de Renzis he gave his last home in a residential district "Monte Mario" on 6' Via Madona du Campilio street, with purpose to help, the young talents and to subserve for the developement of the art and the culture.

The villa had to change in Academy of the ecaboration of the toung opera talents from Bulgaria in stile belcanto. This his gesture was redused after the official communist regime in Bulgarian, which was leaded from selfish and atavistic feelings of malice to his tailent, the redeliest refused to give an area for the Academy, which he dreamed to contructed in Sofia.

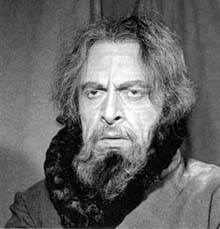

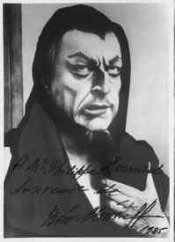

A most difficult man, a man whose conflicts, both on and off stage, are legendary, a staggering presence in life and in art. There are few singers whose careers are so clouded by personal and professional controversy, yet he stands among the greatest of the Century, a towering figure in both the Russian and Italian operatic literature.

Boris Christoff was born in Plovdiv, Bulgaria on 18 May 1914 of a Bulgarian father and a Russian mother. Raina Teodorovna Ivanov was determined that Boris would have an education that stressed his Russian lineage. His lessons included Russian history and language as well as Russian music both at school and at home. However, it must be noted that another biography, one sanctioned by Christoff himself, states that his mother was Bulgarian. The family was very well to do and Boris received the best education available, including a period of study at the University of Sofia. During this time he sang both with the chorus of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral and with the Opera company in "Lohengrin", "Tannhauser" and "Prince Igor". He gave up formal studies in 1939, but continued to be privately tutored with the definite intention of pursuing an operatic career.

Boris made enough money to support himself working as a judge and he occupied much of his spare time singing with the Gusla Chorus. In 1940, after making an enormous impression as the chorus's soloist, he sang his first recital at Sofia's Sala Bulgaria. Four days after the outbreak of World War II, Bulgaria declared its neutrality, so Boris was spared the horror of armed conflict. At some point after his graduation from the University, Boris did serve in the armed forces and was commissioned in the cavalry. He sang regularly in military concerts and was so admired that he was invited to appear on Bulgarian radio as a soloist.

With his military service behind him, with financial help from the Royal Family, and with his family's blessing, on 18 May 1942, his birthday, he emigrated to Italy where, he felt he might better advance his career. The details are unclear but it is certain that sometime during 1942, with help from Giuseppe de Luca, he was introduced to Riccardo Stracciari, who took an immediate interest in the youngster. The great baritone worked with Christoff for nearly two years, tutoring him in the core Italian bass repertoire: Mefistofele, Don Basilio, Philip, Ramfis and Guardiano, as well as Leporello in Mozart's "Don Giovanni". Christoff returned to Sofia for concerts in 1943, and after further study with Stracciari, he moved to Austria, where, during 1944 and 1945 he made several guest appearances in concerts and recital including several broadcasts.

After the defeat of the Axis powers, life began to return to normal and Boris was free to travel wherever he wished. He returned to Italy, where, on 28 December 1945 under the auspices of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, he made what he considered his official stage debut. The program consisted of several Russian songs, Leporello's catalogue aria and Boris Gudonov's "I have attained the highest power". A month later, at Rome's Teatro Adriano he sang Wotan's Farewell with the Santa Cecilia orchestra under Molinari Pradelli and on 12 May 1946 he made his operatic debut as Colline in "La Boheme" at Reggio Calabria.

The performance was so successful that Boris was forced to sing "vecchia zimarra" three times. It was a clamorous and most encouraging beginning, but, as so often happens, the road forward would not be easy. He returned to Rome, where, over a period of three months he appeared in nine concerts including a performance of Bach's "St Matthew's Passion". In July he traveled to Turin for Haydn's "Creation" in a radio broadcast and on the 30th he appeared as Cirillo in Giordano's "Fedora" at Rome's Teatro Quirino. August began with the Pharaoh in Rossini's "Mose" at the Quirino and at the end of the month he moved to the Teatro Adriano for Raimondo in "Lucia di Lammermoor" with Lina Pagliughi. In September, at the Adriano, he repeated Colline and followed these performances with a series of recitals in Rome. On 9 November he returned to the Quirino for Rocco in "Fidelio" and closed out the year with two additional Roman concerts.

On 7 February 1947 Christoff sang an all Brahms recital at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia and the following evening he made his debut at Rome's Teatro dell'Opera as Pimen in "Boris Gudonov". This was a real breakthrough; he had made it into Italy's second theater in a leading, if not starring, role, and the reviews were excellent. At the end of the month he appeared at Palermo's Teatro Massimo in Beethoven's Symphony Number Nine, after which he returned to Rome for Zehrer's "Requiem Mass" and Handel's "Messiah".

In April he traveled to Sardinia for Ramfis, the Conte Des Grieux in "Manon" and Il Cancelliere di Ragusa in Alfano's "Madonna Imperia" at Cagliari. His reviews were unexceptional though they indicated good musicianship, the right temperament and more than just promise. On 4 June, he made his La Scala debut in Brahm's "Deutsches Requiem" with Suzanne Danco under the leadership of Vittorio Gui and he was very well received. At Pescara, in July, he gave a recital, then returned to Rome for three concerts. In the late summer, he returned to Sardinia for Raimondo, Timur and Padre Guardiano at Sassari's Teatro Giardino, again to solid reviews. On 10 September, he appeared in opera at La Scala for the first time when he sang Pimen to the Boris of Tancredi Pasero. The premiere was broadcast throughout Italy, and for the first time, his name appeared in newspapers throughout the country. His reviews were exceptional.

Christoff debuted at Venice's Teatro La Fenice on the 20th in the Mozart "Requiem" and five days later sang in the ?Creation? at Perugia. It was clear that he was very much admired as a vocalist, but that most of Italy was not ready to offer him lucrative opera engagements, yet. He returned to Venice in November for Beethoven?s 9th and on 30 December made his opera debut there as King Mark in "Tristan and Isolde" with Callas, Barbieri, Tasso and Torres under Serafin?s direction. Boris was certain that this engagement would assure his passage from comprimario to star, and his intuitions were correct.

On 17 February 1948 Christoff debuted at Trieste?s Teatro Verdi as Dosifey in "Khovanschina" and a week later assumed the role of Hagen in "Gotterdammerung". He received enormous acclaim in the press and was called almost immediately to substitute for an ailing Tancredi Pasero as Tsar Boris at Cagliari. It was an historic performance, calling forth every superlative imaginable. "Christoff has interpreted this most difficult role with a remarkable personality. The death scene culminated in a display of extraordinary dramatic power and sublime singing." - Corrado Atzeri.

Boris was now hailed as one of Italy's leading singers. Florence saw him as both Dosifey in "Khovanschina" and King Henry in Lohengrin during the festival weeks of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino and in July he debuted at Caracalla as Ramfis. In September he sang in Handel's "Samson" at Perugia and in October he assumed the role of Fiesco for the first time with the forces of Rome's Radio Station. In November with Turin Radio he sang Kaspar in "Der Freischutz" to the Agathe of Caterina Mancini and in December he returned to Florence in "Khovanschina" with Rossi-Lemeni. On 23 December he debuted at Naples Teatro San Carlo as Oroveso in a cast that included Maria Caniglia, Elena Nicolai and Mirto Picchi. Christoff walked off with the reviews. "Majestic, of a grandeur that this theater has not seen since before the War." On the 28th he ended the year at the San Carlo with "Der Freischutz".

1949 began with the historic revival of "I Puritani" at the Fenice with Maria Callas, who stepped into the role of Elvira on five days notice, replacing an indisposed Margherita Carosio. Her performance made headlines throughout Italy. Commentators went to history books to find another occasion in which any singer had alternated such distinctly different roles as the Walkuere Brunnhilde and the Bellini heroine. Christoff was again lauded for the authority of his acting and the magnificence of his voice. On 31 January he appeared as Rocco in "Fidelio" at La Scala and on 9 February he sang Dosifey partnered again by Rossi-Lemeni. Late in the month he returned to Venice for Dosifey and in March he sang in Cimarosa's "Il Matrimonio Segreto" at La Scala.

The Milan public saw him as Guardiano on 22 March in a cast that included Elisabetta Barbato, Giulietta Simionato, Mario Filippeschi and Paolo Silveri, and after several concerts in the spring, he appeared at the Verona Arena on 21 July in "Lohengrin" with Renata Tebaldi, Nicolai, Gianni Poggi and Torres. At Salzburg, he appeared in the Verdi Requiem and Beethoven's Symphony No.9 and in September he sang Seneca in "L'Incoronazione di Poppea" at Vicenza. The opera was repeated intact at Venice's Fenice on 16 September. In October he sang Banquo for the first time for Turin Radio and on 19 November he debuted at Covent Garden as Tsar Boris. The London Times reported "the fact that Christoff sang the role in Russian was a small price to pay for such a fine interpretation". A later article sported the banner headline "Covent Garden finds a new Chaliapin". Harold Rosenthal stated that London had been privileged to see his debut in the role and that he had previously sung only Pimen and Varlaam. Neither statement was true; he had previously sung Boris and he had not sung Varlaam. In fact, he sang Varlaam only once, in a semistaged television broadcast from Copenhagen in 1971, a performance in which he also sang Boris and Pimen. On the 25th he repeated the Beethoven 9th at Royal Albert Hall with Schwarzkopf, J. Watson and Schock under von Karajan's direction. During his stay he made his first recordings for HMV. He closed out the year with another triumph as Tsar Boris at La Scala.

Boris Christoff, Nino Stinco, Giulieta Simionato, Ferruciio Tagliavini, Paulo Fortes, Guilhermo Damiano

On 21 January 1950 Boris appeared in "Simon Boccanegra" at the Fenice with Mancini, Penno and Tagliabue and on 4 February he sang Gounod's Mephistopheles for the first time. His Venice season ended on 19 February as Rocco in "Fidelio". The Naples San Carlo presented him in Tannhauser on 12 March with Tebaldi, Hans Beirer, and Tagliabue and later in the month he returned to Cagliari for "Il Matrimonio Segreto" and "Khovanschina". In April he repeated Dosifey at La Scala and on 27 May, for the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, he sang Philip in "Don Carlo". The stellar cast of Caniglia, Stignani, Picchi, Silveri and Neri was conducted by Tullio Serafin. On 15 June, at Florence, he sang Agammemnon in Gluck's "Iphiginie in Aulide" and at the end of the month Boris traveled to Berne for "La Forza del Destino". At La Scala he appeared in Beethoven's "Missa Solemnis", Bach's Mass in B minor, and in Brahms "Deutsches Requiem" with Victoria de los Angeles, all of which received unqualified praise.

It was time for Christoff's Met debut. Rudolf Bing had decided to inaugurate his era with "Don Carlo" and he invited Boris to debut on the opening night. The United States government had just enacted the McCarran Immigration act by which citizens of many countries, including Bulgaria, were barred from entry into the country. In fact, Christoff was accused of being a Russian, from Moscow, and he naively declared in a sworn statement that he had never even been to Moscow. The immigration service would not relent despite intervention from Sol Hurok and other high placed dignitaries. With a short time remaining until the first performance, Bing reluctantly gave up hope that the issue would be resolved and offered the role to Cesare Siepi. The production and the libretto were protested as subversive, anti Catholic and pro Communist by many Roman Catholics and some far right politicians. The fact that Christoff had been engaged only contributed to the controversy and there were pickets at the Met for a considerable period of time before the premiere and during its run. Boris Christoff would sing in the United States six years later, but his subsequent negotiations with the Met amounted to nothing, and he never did appear in that theater.

The Met's loss was posterity's gain, because on 20 November 1950 he recorded the role of Gurnemanz in a most moving performance of Parsifal for Italian Radio. Maria Callas sang a surpassing Kundry and among the Flower Maidens was Lina Pagliughi. It has been released in several editions and is among the author?s favorite recordings. On 23 December he sang the role of Cerevik in "La Fiera di Sorocinski" at the Rome Opera and two weeks later sang in "La Sonnambula" at that theater with Carosio and Cesare Valletti. On 6 February he recorded both Galitsky and Konchak in "Prince Igor" for Italian Radio and later in the month he returned to the Rome Opera for "Ernani" with Mancini, Penno and Silveri.

On 26 February he repeated Gudonoff at London's Covent Garden and made additional recordings for HMV. March found him at Cagliari for the Manzoni Requiem and "Don Carlo" and in April he returned to La Scala for Galitsky and Konchak. In May he sang Procida for the first time in a spectacular production at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. Callas was Elena, Kokolios sang Arrigo and Enzo Mascherini sang Montforte. It is preserved on record and is a truly grand performance, even if the tenor leaves something to be desired. He continued his season at Florence in Haydn's "Orfeo ed Euridice", again with Callas, after which he took a long break from performing.

On 6 September he debuted as Philip at Rio de Janeiro's Teatro Municipal and on the 16th he sang Oroveso to the Norma of Callas, the Adalgisa of Nicolai and the Pollione of Picchi. On 9 October he debuted at Antwerp as Tsar Boris and on 3 November he sang Oroveso at Catania. Callas, Simionato and Gino Penno rounded out the cast and the Sicilian press declared the revival the most satisfactory in this Century. Six days later he sang in "I Puritani" with Callas, after which he traveled to Florence for his first assumption of the title role in Rossini's "Mose". Mancini, Carteri and Gustavo Gallo were his partners. On 7 December he opened the La Scala season as Procida, again with Callas who was making her official debut at the theater.

On New Years Day 1952 he debuted at Barcelona's Liceo as Tsar Boris and on the 17th he returned to Rome for "Der Freischutz" with Mancini, Simionato and Franco Albanese. On 21 March he recorded Boris Gudonoff for Rome's Radio Station and on 16 April he recorded the "Deutsches Requiem" with Carteri. On 27 July he performed Boito?s Mefistofele for the first time when he debuted at Naples outdoor Arena Flegrea. In the autumn Bologna heard him in "Lohengrin" with Carteri, Nicolai and Penno and in "Simon Boccanegra" with Mancini, Penno and his brother in law, Tito Gobbi. Theirs was not a good relationship, and as we will later see, there were public feuds, which both men in later years attempted to play down. On 14 December he repeated Tsar Boris for the Rome Opera and opened the New Year in the role at Modena's Teatro Comunale.

In 1953, Boris sang Boris at Venice, Cagliari, the Paris Opera, and at Nice. He also sang in "Faust" at Rimini, "Don Carlo" at Bologna and "Norma" with Callas, Nicolai and Corelli at Trieste. Il Giornale di Trieste: "Boris Christoff defined with unquestionable authority the beauty and vigor of his voice and the dignity of his acting". Boris opened 1954 with "Don Carlo" at Venice and on 13 February he sang Gounod's "Mephisto" at La Scala with Schwarzkopf, Poggi, and Mascherini. In March, the Rome Opera presented Christoff, Mancini, Nicolai, Corelli and Gobbi in a stunning and hugely successful production of "Don Carlo".

On 8 June, Boris sang in Tschaikovsky's "Mazeppa" at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino with Magda Olivero, and at Caracalla, in July, he sang Zaccaria in "Nabucco" with Mancini, Albanese and Gobbi. August found him at Naples for "Aida" with Cerquetti, Nicolai, Penno and Giangiacomo Guelfi and for "Faust". In November he sang Ivan in Rimsky-Korsakov's opera on Milan's Radio network and in December he returned to Florence for "Nabucco" and "La Boheme".

In early January 1955 Boris sang both Galitzky and Konchak at the Rome Opera and began rehearsals for "Medea" with Maria Callas. Callas, when told that Boris would be Creonte, protested that she should have known earlier, claiming veto rights over casting until shown her contract. Christoff protested cuts in the score, stating that he was left with one third of the role, and that he would not sing unless the cuts were restored. He furthermore asserted that the Meneghinis were behind it. Meneghini, for his part, hired a claque to disrupt Christoff's scenes, and on the first night, 22 January, a large number of people did exactly that at the end of Creonte's invocation. There were fights in the balcony and police had to be called to the upper reaches of the theater to restore some semblance of order. Maria was protested at the end of "Deh tuoi Figli" and again, there was a delay. At the end of act two, as Maria approached the proscenium for a solo curtain call, Boris blocked her way and refused to allow her passage. "Either we all go out together, or no one goes out". The applause was frantic and interminable but no one appeared on the stage. Finally, the theater's manager explained to a large group of onlookers and reporters "Oh it's nothing serious. Just a Greco-Bulgarian war". Callas ultimately retreated to her dressing room. They completed the engagement and never sang together again.

In 1955 Boris added Handel's "Judas Maccabeus", "Acis and Galatea" and "Giulio Cesare" to his repertoire and in 1956, he sang Sarastro at Naples and Don Basilio at Rio de Janeiro for the first times. He also debuted in the United States at the San Francisco War Memorial on 25 September as Tsar Boris and a few nights later he sang in "Simon Boccanegra" with Renata Tebaldi and Leonard Warren. The company performed both operas in Los Angeles. Arthur Bloomfield's "The San Francisco Opera" - "When Christoff arrived, he did not like the production at all. Furthermore, he had an argument with Steinberg who had replaced Von Matacic as conductor and left a rehearsal to sulk in his dressing room. Swallowing his dissatisfaction somewhat, he ultimately did perform as advertised". On 10 December he sang in New York for the first time at the NBC studios. In a concert that included Marian Anderson, de los Angeles and Richard Tucker, Christoff sang Boris's Farewell and Death. On 26 December he returned to Rome for "Iris" with Clara Petrella and Giuseppe di Stefano. The performance has been preserved on CD and is among the favorite versions of that opera for a large number of people.

In 1955 Boris added Handel's "Judas Maccabeus", "Acis and Galatea" and "Giulio Cesare" to his repertoire and in 1956, he sang Sarastro at Naples and Don Basilio at Rio de Janeiro for the first times. He also debuted in the United States at the San Francisco War Memorial on 25 September as Tsar Boris and a few nights later he sang in "Simon Boccanegra" with Renata Tebaldi and Leonard Warren. The company performed both operas in Los Angeles. Arthur Bloomfield's "The San Francisco Opera" - "When Christoff arrived, he did not like the production at all. Furthermore, he had an argument with Steinberg who had replaced Von Matacic as conductor and left a rehearsal to sulk in his dressing room. Swallowing his dissatisfaction somewhat, he ultimately did perform as advertised". On 10 December he sang in New York for the first time at the NBC studios. In a concert that included Marian Anderson, de los Angeles and Richard Tucker, Christoff sang Boris's Farewell and Death. On 26 December he returned to Rome for "Iris" with Clara Petrella and Giuseppe di Stefano. The performance has been preserved on CD and is among the favorite versions of that opera for a large number of people.

In May1957 he debuted as Dosifey at Lisbon's Sao Carlos and later sang in "Simon Boccanegra" there with Pobbe, Gobbi and Corelli. On May 25 he recorded Massenet's "Don Quichotte" at Milan with Teresa Berganza and in June he returned to the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino for "Ernani" with Cerquetti, Del Monaco and Bastianini. In September, Cerquetti, Simionato, Miranda Ferraro, Protti and Christoff record "La Forza del Destino" for RAI. The Convent Scene is among the great moments in our recorded legacy, and, though flawed, is of a grandeur that is breathtaking. So says the author. Boris returned to the United States in October for a debut at New Orleans as Tsar Boris and followed that with concerts at Miami, Washington, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. On 22 November he debuted as Philip at the Chicago Lyric with Cerquetti, Nell Rankin, Brian Sullivan and Tito Gobbi. Paul Fornatar remembers - "I was fortunate enough to see everything Christoff did in Chicago. Sublime would describe the total package of voice, acting and makeup. He was the role he was singing and I think he might have considered himself a great artist - that was the magnetism that crossed the footlights. The voice never recorded as full and penetrating as it was in the house. It wasn't a large voice but a dark arrow which penetrated to the marrow".

1958 recorded one of the most infamous episodes in Christoff's professional life. At the Rome Opera during a rehearsal of Don Carlo, as Philip was in the act of confronting his son in the "Auto da Fe", Christoff?s sword came crashing down upon Franco Corelli's own, and blows were struck. Tito Gobbi describes the scene "It is a terrific moment and I still see Boris, as the King, meeting the uplifted sword of the young and handsome Corelli and the fierce blows they exchanged before I stepped hastily forward to prevent quite a serious accident. Recalling this tempestuous rehearsal, I cannot help asking myself whether some magic from the scenic suggestion affected them or some private grudge provoked this realistic encounter". Christoff retreated from the theater and withdrew from the production, declaring that Corelli was devoid of artistic integrity. Mario Petri replaced him and the revival was, despite the defection, an enormous success.

1958 recorded one of the most infamous episodes in Christoff's professional life. At the Rome Opera during a rehearsal of Don Carlo, as Philip was in the act of confronting his son in the "Auto da Fe", Christoff?s sword came crashing down upon Franco Corelli's own, and blows were struck. Tito Gobbi describes the scene "It is a terrific moment and I still see Boris, as the King, meeting the uplifted sword of the young and handsome Corelli and the fierce blows they exchanged before I stepped hastily forward to prevent quite a serious accident. Recalling this tempestuous rehearsal, I cannot help asking myself whether some magic from the scenic suggestion affected them or some private grudge provoked this realistic encounter". Christoff retreated from the theater and withdrew from the production, declaring that Corelli was devoid of artistic integrity. Mario Petri replaced him and the revival was, despite the defection, an enormous success.

The year also found Christoff's in two of his most celebrated performances, both preserved on LP and CD. At Naples in March, he sang in "La Forza del Destino" with Tebaldi, Dominguez, Corelli, Bastianini and Capecchi and in May he appeared in the historic Visconti production of "Don Carlo" in London with Brouwenstijn, Barbieri, Vickers and Gobbi. Nick Palmer remembers - "I guess that I went to some 20 performances with Christoff, Boris and Don Carlo mainly. Irrevocably etched in my memory - his curtain calls. I never saw him acknowledge the audience with other than a grave inclination of his head. I never saw him even lift his arms. I never saw even the remotest hint of a smile. Even amidst the audience cacaphony he stood nearly immobile - almost arrogant". On 2 December he made his Carnegie Hall debut in a concert version of "Mose" with the American Opera Society and on 18 December he repeated the role at La Scala.

In the spring of 1959, after further performances of "Mose" at Rome, he returned to La Scala for "A Life for the Tsar" with Scotto, Cossotto and Gianni Raimondi, and in June, Boris sang for the Milanese in "Iphiginie in Aulide" with Simionato, Adriana Lazzarini and Mirada Ferraro. In August at Rome he recorded the Verdi Requiem with Vartenissian, Cossotto and Fernandi and in September he recorded a recital of Tschaikovsky songs at Paris. Christoff ended the year with Boris Gudonoff in London.

In the spring of 1959, after further performances of "Mose" at Rome, he returned to La Scala for "A Life for the Tsar" with Scotto, Cossotto and Gianni Raimondi, and in June, Boris sang for the Milanese in "Iphiginie in Aulide" with Simionato, Adriana Lazzarini and Mirada Ferraro. In August at Rome he recorded the Verdi Requiem with Vartenissian, Cossotto and Fernandi and in September he recorded a recital of Tschaikovsky songs at Paris. Christoff ended the year with Boris Gudonoff in London.

January of 1960 found Boris in Philadelphia and New York for concerts, and in February he returned to La Scala for Tsar Boris, followed by "Parsifal". He sang in "Don Carlo" at Salzburg in August, and in October, he returned to Chicago as Philip with Roberti, Simionato, Tucker and Gobbi. The arguments between the two brothers in law were horrific and Gobbi said in a later interview "men who are secure in themselves and know what they want, will disagree". The local newspapers referred to gross epithets that were unprintable. The theater's management attempted to mitigate the damage by painting a picture of two men who misunderstood certain directions in the production and Gobbi later stated that "we basically argued over two dogs in one of the scenes, nothing more than that". The performances were considered superb and the incident was all but dropped.

On 13 December, Boris returned to La Scala for "Don Carlo" with Stella, Simionato, Labo and Bastianini. The newcomer, Nicolai Ghiaurov, was assigned the role of the Grand Inquisitor. So much anger passed between the two men that physical restraint was threatened on more than one occasion. Ghiauroff was admired and supported by the Communist regime in Bulgaria, and Christoff was so despised, that when his father died earlier in the year, he was denied a visa to attend the funeral. Audiences were mesmerized by the palpable effect of their intense animosity, most thinking that it was the product of a dramatic brilliance engendered by the opera. The tensions became unbearable, and Christoff announced that the theater was not large enough to accommodate both men. He was very specific in his demand that one or the other would have to leave. The Scala management chose not to capitulate and offered Boris the opportunity to honor his contract with "Parsifal" which was already in rehearsal with Rita Gorr, Sandor Konya, and Gustave Neidlinger. He chose to sing Gurnemanz. On 11 May, 1961 the doors of La Scala were closed behind Boris Christoff, never again to be opened.

On 13 December, Boris returned to La Scala for "Don Carlo" with Stella, Simionato, Labo and Bastianini. The newcomer, Nicolai Ghiaurov, was assigned the role of the Grand Inquisitor. So much anger passed between the two men that physical restraint was threatened on more than one occasion. Ghiauroff was admired and supported by the Communist regime in Bulgaria, and Christoff was so despised, that when his father died earlier in the year, he was denied a visa to attend the funeral. Audiences were mesmerized by the palpable effect of their intense animosity, most thinking that it was the product of a dramatic brilliance engendered by the opera. The tensions became unbearable, and Christoff announced that the theater was not large enough to accommodate both men. He was very specific in his demand that one or the other would have to leave. The Scala management chose not to capitulate and offered Boris the opportunity to honor his contract with "Parsifal" which was already in rehearsal with Rita Gorr, Sandor Konya, and Gustave Neidlinger. He chose to sing Gurnemanz. On 11 May, 1961 the doors of La Scala were closed behind Boris Christoff, never again to be opened.

In August Boris debuted at the King's Theater in Edinburgh as Don Basilio and in September he recorded "Gallo d'Oro" ( The Golden Cockerel ) for Rome Radio. He returned to Chicago in October for "Mefistofele", "La Forza del Destino" and "Barbiere di Siviglia" and ended the year at Naples as Philip.

In August Boris debuted at the King's Theater in Edinburgh as Don Basilio and in September he recorded "Gallo d'Oro" ( The Golden Cockerel ) for Rome Radio. He returned to Chicago in October for "Mefistofele", "La Forza del Destino" and "Barbiere di Siviglia" and ended the year at Naples as Philip.

In March 1962 he debuted at the Vienna Staatsoper in "Don Carlo" with Sena Jurinac, Simionato, Labo, Eberhardt Waechter and Hans Hotter and in May he returned for "La Forza del Destino". In October, Chicago saw him in "Prince Igor" and "La Boheme" and in December Boris sang in Verdi's "Attila" for the first time at Florence's Teatro Comunale.

In April 1963 Christoff debuted at Hamburg as Philip and in May he sang in "Faust" at Geneva. Chicago hosted him as Zaccaria, Pizarro and Don Basilio in the autumn, and he ended the year at Florence with Tsar Boris. In January 1964 Boris sang Pogner at the Rome opera, and after appearances at Paris and Vienna, he sang in "Prince Igor" at Rome in September.

It was discovered that Boris had a brain tumor and that immediate surgery would be necessary if his life were to be saved. The operation was successful but it was to be several weeks before it was certain that there was no permanent physical or mental damage. Public statements were withheld until just before Christmas 1964 at which point it was known that Boris would be able to resume a normal life including a career on the stages of the world, should he so choose. There is a most touching letter to Boris from his mother, a Christmas note, in which she says that she always knew that God was, after all, a good God and that she had placed her "Angel" in his care. She was still in Bulgaria and he in the West, a source of great emotional pain for both. Boris? recuperation was slow, but he did resume his career in 1965, though at a reduced pace. When he appeared, it was in some of his most demanding music, including the Manzoni Requiem, Tsar Boris and Giulio Cesare.

He returned to the United States on 16 March 1966 as "Boris Gudonov" with the Boston Opera Company. Bill Fregosi, who has been most gracious in offering a great deal of information for this article, remembers - "I caught his always powerful Boris, albeit somewhat past his prime, in a Sarah Caldwell production in Boston which made the cleverest imaginable use of a miniscule stage to suggest the grandeur and scale of the Kremlin. He was magnetic and deeply moving. Audience reaction was tremendous".

He returned to the United States on 16 March 1966 as "Boris Gudonov" with the Boston Opera Company. Bill Fregosi, who has been most gracious in offering a great deal of information for this article, remembers - "I caught his always powerful Boris, albeit somewhat past his prime, in a Sarah Caldwell production in Boston which made the cleverest imaginable use of a miniscule stage to suggest the grandeur and scale of the Kremlin. He was magnetic and deeply moving. Audience reaction was tremendous".

The author remembers that both performances were sold out and that he was discouraged by personnel at the box office from making the trip from New York. There was a waiting list of hundreds of people for any tickets that might become available. So, I was to wait another fourteen years before I would see Boris Christoff, for the only time in my life.

In December 1966, Boris sang in "Don Carlo" at the Paris Opera and in September of 1967 he returned for additional performances. Boris beloved mother died in 1967 and he was allowed to return to Sofia for her funeral. In 1968 he sang for the first time in "Robert le Diable" for the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino with Giorgio Merighi and Renata Scotto, and in November he appeared at London's Drury Lane Theater in "Nabucco". Christoff continued to learn new roles, and in 1972, he sang in Nielsen's "Saul and David" at Copenhagen and in Verdi's "I Masnadieri" at Rome. Again, at Rome, in 1977, he sang Henry VIII in "Anna Bolena" with Leyla Gencer as the doomed heroine. Before it was over, he was also to appear at Amsterdam, The Hague, Budapest, Wiesbaden, Malta, Madrid, Birmingham (England), Cologne, Munich, Rejkjavik, and in a final concert at the Accademia di Bulgaria in Rome on 22 June 1986.

Boris Christoff never sang before a live audience in his homeland after his debut at Rome in 1945.

On 24 March 1980, I finally had the privilege of seeing Boris at Carnegie Hall. He sang Banquo's "Come del ciel precipita", "Ella giammai m'amo" and Mussorgsky's "Songs and Dances of Death". He closed the program with "Boris's Farewell and Death". Murray Schlanger remembers - "It was one of my great nights of opera going??Christoff was dressed in white tie and tails and although I remember the house being darkened, I believe the stage remained lighted with no effort to set a mood through effect by artificial means. From the moment that unique voice uttered its first note, it was clear to me that I was living a dream that I never had expected to realize. I was so very grateful to be able to participate in an event that somehow I knew was something of a completion of a career of great stature".

On 24 March 1980, I finally had the privilege of seeing Boris at Carnegie Hall. He sang Banquo's "Come del ciel precipita", "Ella giammai m'amo" and Mussorgsky's "Songs and Dances of Death". He closed the program with "Boris's Farewell and Death". Murray Schlanger remembers - "It was one of my great nights of opera going??Christoff was dressed in white tie and tails and although I remember the house being darkened, I believe the stage remained lighted with no effort to set a mood through effect by artificial means. From the moment that unique voice uttered its first note, it was clear to me that I was living a dream that I never had expected to realize. I was so very grateful to be able to participate in an event that somehow I knew was something of a completion of a career of great stature".

The author remembers that, as he walked toward Carnegie Hall, he was besieged by people with money to spend, any amount for a ticket. I was not about to part with my treasure. It was as though a circle was about to close. The last of the great heroes of my youth was, in a few moments, to give me one of the great thrills of my life, and he did not disappoint, in any way. The concert is preserved on CD and I turn to it from time to time so that I can remember.

On 23 June 1993 Boris life was spent. His body was returned to the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral where he had first sung as a boy, for a state funeral. The Communist Hierarchy insisted upon the honor of being pallbearers, they who had so vilified him in life. It is recorded and has been relayed to me by Barry Brenesal - "so upset were some of the mourners that there was hissing in the Cathedral for the first time in recorded memory". Even in death, Boris Christoff aroused "passions" that could not be contained, just as his own could not be contained in life. To his immortal memory!